Jenkin Powell

By Carl Kirby in Cwmafan appreciation group

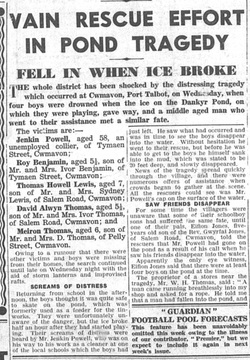

TWO days after Jenkin Powell drowned trying to save four young boys from a frozen pond in Cwmavon, their inquest was held at the village’s Calfaria Chapel.At the climax of an emotionally-charged hearing, the coroner concluded: “Nothing in the history of Cwmavon will compare with the heroism of Jenkin Powell. “Although other things will be forgotten, his last act will live forever in the memory of the village.”Sixty-nine years later and the words remain as poignant as ever.

At an informal ceremony on Monday morning the park built on the scene of the tragedy was renamed in his honour – Parc Siencyn Powell.The memory of his heroism lives on in the collective memory of the close-knit community, but the facts about that cruel winter’s day in 1940 have been distorted with time. ANDREW PUGH looks back through the Guardian archives to see how the incident was reported

At 3.30pm on Wednesday, January 24, 1940, a crowd of schoolchildren hurriedly made their way home at the end of a long school day.

Among them were four boys whose young lives were about to be cut short in a tragedy that would scar the village of Cwmavon for generations.

They were Roy Benjamin, 7, son of Mr and Mrs Ivor Benjamin of Tymaen Street; Howard Lewis, 8, son of Mr and Mrs Sidney Lewis of Salem Row; Alwyn Thomas, 5, son of Mr and Mrs Ivor Thomas, Pelly Street; and Meiron Thomas, 6, son of Mr and Mrs David Thomas, also of Pelly Street.

Their route home led past a pond used as a feeder for the nearby tinplate mills. The pond had frozen over during a bitterly cold winter.

The pond was a source of fascination for the village’s youngsters. They would fish there in the summer and skate there in the winter.

The pond, owned by the Jersey Estate, would later be described as a kind of no man’s land – which was the reason why it had never been fenced off.

Half-an-hour hour after leaving school two of the boys were seen skating arm-in-arm on the fragile surface by a school friend six-year-old Eifion Jones, of Salem Road.

He would later tell the inquest: “I watched the boys for some time. When I saw them disappear in the water I was frightened and ran to the police station for help.”

But Eifion wasn’t the only one who saw the unfolding tragedy.

Ex-collier Jenkin Powell, 59, of Tymaen Terrace, was on his way to the school where he worked as a caretaker.

Mr Powell heard the children’s frantic cries and, looking across the pond, saw them slowly disappear.

Without hesitation he went to the rescue but the pond was in a treacherous state – as well as the freezing water, he had to fight his way through mud, slime and reeds as deep as 20-feet.

Before he could reach them he too sank, only his cloth cap remaining on the pond’s surface.

Humphrey Gilbert Prosser, of Gladys Street, Aberavon, was passing the pond on his way home from work at the Dyffryn Rhondda Colliery when he heard screaming from the bank.

When he arrived a man asked him to give him a hand and Mr Prosser bravely waded into the water, where he saw Mr Powell’s motionless body.

Mr Prosser began sinking, then climbed out and tried entering from another side, but the mud and reeds were too much for him and he went to fetch a rope.

The next man to arrive was Constable Mog Hopkins, who entered the water with a rope tied around his waste but also became stuck.

At 5pm, Brinley Cockwell, of Cattybrook Terrace, made a makeshift raft from planks of wood and finally managed to pull out Jenkins’ body using a grappling iron.

By now the fire service had arrived and the rescue parties worked on the improvised rafts and guided their grappling irons by the light of storm lanterns.

It wasn’t until 7pm that all the bodies were finally recovered.

A doctor J R Hughes had desperately tried resuscitating the bodies as they were pulled from the water one by one, but to no avail.

News of the disaster had spread through the village and hundreds of people were now gathered around the pond, fuelling rumours there were more bodies, and so the search continued into the night.

The next day the pond was drained and the area extensively searched, though thankfully no more bodies were found.

The inquest was held on Friday, January 26, by coroner Mr B Edward Howe, father of Geoffrey Howe, who would later become Margaret Thatcher’s longest-serving cabinet minister.

The surveyor to the Jersey Estate, Cyril Lloyd, said the company was “not in the custom” of fencing ponds adding: “It was a sort of no man’s land. Adjoining property that had been acquired by other people, while the pathway has become public by usage.”

Today the estate would at the very least be facing negligence charges, or at worst corporate manslaughter.

But on that day they were barely given a slap on the wrist.

Mr Howe told the representative:“I am very much obliged to Mr Lloyd for explaining the position of the Jersey Estate, because I think now this unfortunate affair has happened, the Estate might consider themselves under some form of moral duty to see the pond is protected, on one side where it is so deep.

“I am not saying that there is any duty, but I thought they might consider the question of putting some form of fence, as children are in the habit of frequenting the pond.”

He went on to commend Mr Prosser, Constable Hopkins and Mr Cockwill for doing “everything humanly possible” to help the rescue effort.

He concluded: “The hero of this terrible tragedy was undoubtedly Jenkin Powell, who, although 59 years of age did not hesitate to go in to the water in the hope that he could do something to help the children who had fallen in.”

Islwyn Morgan, director of education, had known Mr Powell well.

In an emotional address he told the hearing: “The four little mites have been uprooted ruthlessly and hurled into eternity. The calamity has shocked the whole borough, and I can quite understand why so much lamentation and grief prevail today.

“I have known Jenkin Powell all my life. He was a quiet man living a simple life, and in the end he reached exceeding heights and died a hero.”

On Sunday, January 28, 20,000 people descended on the village lining the route to Pantdu cemetery where four of the bodies were buried .

Many were from neighbouring towns and villages and the cortege was more than five miles long, including 2,000 children holding posies of flowers.

At 2.30pm simultaneous services were held at all five homes and half-an-hour later the mourners gathered at Bethania Chapel.

The body of Mr Powell was taken away on a large hearse while the plain oak coffins of the four boys were carried by their young school friends.

Eight-year-old Howard Lewis was buried at the old church yard and the rest were taken to the cemetery at Pantdu.

It was far too small to accommodate the thousands of mourners who instead stood on the hillside and along the main road.

At 10am on Monday, March 2, 2009, relatives, friends, villagers and schoolchildren once again gathered in the village to remember the dead.

They included Ron Lyttle, 75, cousin of Roy Benjamin, Eddie Cockwell, nephew of Brinley Cockwell, and relations of Jenkin Powell.

At 10.20pm the cover was taken off and the new sign revealed with the help of a child from Cwmavon Infants School, four-year-old Madison Williams.

Madison is the grandaughter of Diane Williams – the brother of one of the young victims, Howard Lewis, who she never met.

Finally the park was blessed by a local vicar – and in the words of the coroner, Mr Howe, the village of Cwmavon had shown it would never forget the memory of Jenkin Powell.

TWO days after Jenkin Powell drowned trying to save four young boys from a frozen pond in Cwmavon, their inquest was held at the village’s Calfaria Chapel.At the climax of an emotionally-charged hearing, the coroner concluded: “Nothing in the history of Cwmavon will compare with the heroism of Jenkin Powell. “Although other things will be forgotten, his last act will live forever in the memory of the village.”Sixty-nine years later and the words remain as poignant as ever.

At an informal ceremony on Monday morning the park built on the scene of the tragedy was renamed in his honour – Parc Siencyn Powell.The memory of his heroism lives on in the collective memory of the close-knit community, but the facts about that cruel winter’s day in 1940 have been distorted with time. ANDREW PUGH looks back through the Guardian archives to see how the incident was reported

At 3.30pm on Wednesday, January 24, 1940, a crowd of schoolchildren hurriedly made their way home at the end of a long school day.

Among them were four boys whose young lives were about to be cut short in a tragedy that would scar the village of Cwmavon for generations.

They were Roy Benjamin, 7, son of Mr and Mrs Ivor Benjamin of Tymaen Street; Howard Lewis, 8, son of Mr and Mrs Sidney Lewis of Salem Row; Alwyn Thomas, 5, son of Mr and Mrs Ivor Thomas, Pelly Street; and Meiron Thomas, 6, son of Mr and Mrs David Thomas, also of Pelly Street.

Their route home led past a pond used as a feeder for the nearby tinplate mills. The pond had frozen over during a bitterly cold winter.

The pond was a source of fascination for the village’s youngsters. They would fish there in the summer and skate there in the winter.

The pond, owned by the Jersey Estate, would later be described as a kind of no man’s land – which was the reason why it had never been fenced off.

Half-an-hour hour after leaving school two of the boys were seen skating arm-in-arm on the fragile surface by a school friend six-year-old Eifion Jones, of Salem Road.

He would later tell the inquest: “I watched the boys for some time. When I saw them disappear in the water I was frightened and ran to the police station for help.”

But Eifion wasn’t the only one who saw the unfolding tragedy.

Ex-collier Jenkin Powell, 59, of Tymaen Terrace, was on his way to the school where he worked as a caretaker.

Mr Powell heard the children’s frantic cries and, looking across the pond, saw them slowly disappear.

Without hesitation he went to the rescue but the pond was in a treacherous state – as well as the freezing water, he had to fight his way through mud, slime and reeds as deep as 20-feet.

Before he could reach them he too sank, only his cloth cap remaining on the pond’s surface.

Humphrey Gilbert Prosser, of Gladys Street, Aberavon, was passing the pond on his way home from work at the Dyffryn Rhondda Colliery when he heard screaming from the bank.

When he arrived a man asked him to give him a hand and Mr Prosser bravely waded into the water, where he saw Mr Powell’s motionless body.

Mr Prosser began sinking, then climbed out and tried entering from another side, but the mud and reeds were too much for him and he went to fetch a rope.

The next man to arrive was Constable Mog Hopkins, who entered the water with a rope tied around his waste but also became stuck.

At 5pm, Brinley Cockwell, of Cattybrook Terrace, made a makeshift raft from planks of wood and finally managed to pull out Jenkins’ body using a grappling iron.

By now the fire service had arrived and the rescue parties worked on the improvised rafts and guided their grappling irons by the light of storm lanterns.

It wasn’t until 7pm that all the bodies were finally recovered.

A doctor J R Hughes had desperately tried resuscitating the bodies as they were pulled from the water one by one, but to no avail.

News of the disaster had spread through the village and hundreds of people were now gathered around the pond, fuelling rumours there were more bodies, and so the search continued into the night.

The next day the pond was drained and the area extensively searched, though thankfully no more bodies were found.

The inquest was held on Friday, January 26, by coroner Mr B Edward Howe, father of Geoffrey Howe, who would later become Margaret Thatcher’s longest-serving cabinet minister.

The surveyor to the Jersey Estate, Cyril Lloyd, said the company was “not in the custom” of fencing ponds adding: “It was a sort of no man’s land. Adjoining property that had been acquired by other people, while the pathway has become public by usage.”

Today the estate would at the very least be facing negligence charges, or at worst corporate manslaughter.

But on that day they were barely given a slap on the wrist.

Mr Howe told the representative:“I am very much obliged to Mr Lloyd for explaining the position of the Jersey Estate, because I think now this unfortunate affair has happened, the Estate might consider themselves under some form of moral duty to see the pond is protected, on one side where it is so deep.

“I am not saying that there is any duty, but I thought they might consider the question of putting some form of fence, as children are in the habit of frequenting the pond.”

He went on to commend Mr Prosser, Constable Hopkins and Mr Cockwill for doing “everything humanly possible” to help the rescue effort.

He concluded: “The hero of this terrible tragedy was undoubtedly Jenkin Powell, who, although 59 years of age did not hesitate to go in to the water in the hope that he could do something to help the children who had fallen in.”

Islwyn Morgan, director of education, had known Mr Powell well.

In an emotional address he told the hearing: “The four little mites have been uprooted ruthlessly and hurled into eternity. The calamity has shocked the whole borough, and I can quite understand why so much lamentation and grief prevail today.

“I have known Jenkin Powell all my life. He was a quiet man living a simple life, and in the end he reached exceeding heights and died a hero.”

On Sunday, January 28, 20,000 people descended on the village lining the route to Pantdu cemetery where four of the bodies were buried .

Many were from neighbouring towns and villages and the cortege was more than five miles long, including 2,000 children holding posies of flowers.

At 2.30pm simultaneous services were held at all five homes and half-an-hour later the mourners gathered at Bethania Chapel.

The body of Mr Powell was taken away on a large hearse while the plain oak coffins of the four boys were carried by their young school friends.

Eight-year-old Howard Lewis was buried at the old church yard and the rest were taken to the cemetery at Pantdu.

It was far too small to accommodate the thousands of mourners who instead stood on the hillside and along the main road.

At 10am on Monday, March 2, 2009, relatives, friends, villagers and schoolchildren once again gathered in the village to remember the dead.

They included Ron Lyttle, 75, cousin of Roy Benjamin, Eddie Cockwell, nephew of Brinley Cockwell, and relations of Jenkin Powell.

At 10.20pm the cover was taken off and the new sign revealed with the help of a child from Cwmavon Infants School, four-year-old Madison Williams.

Madison is the grandaughter of Diane Williams – the brother of one of the young victims, Howard Lewis, who she never met.

Finally the park was blessed by a local vicar – and in the words of the coroner, Mr Howe, the village of Cwmavon had shown it would never forget the memory of Jenkin Powell.